The invisible connection between groundwater and sanitation

The world faces a global sanitation crisis as nearly 4.2 billion people, or more than half of the global population, are still living without access to safely managed sanitation services, which include both sewered and non-sewered/on-site sanitation systems (OSSs). The world is urbanising rapidly: more than half of the global population currently resides in cities and towns. In Africa, particularly, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) – considered the world’s fastest urbanising region – the global share of African urban dwellers is projected to grow from 11.3% in 2010 to 20.2% by 2050. Unfortunately, rapidly urbanising cities and towns in low- and middle-income countries are drastically falling behind in the goal of universal safely managed sanitation services.

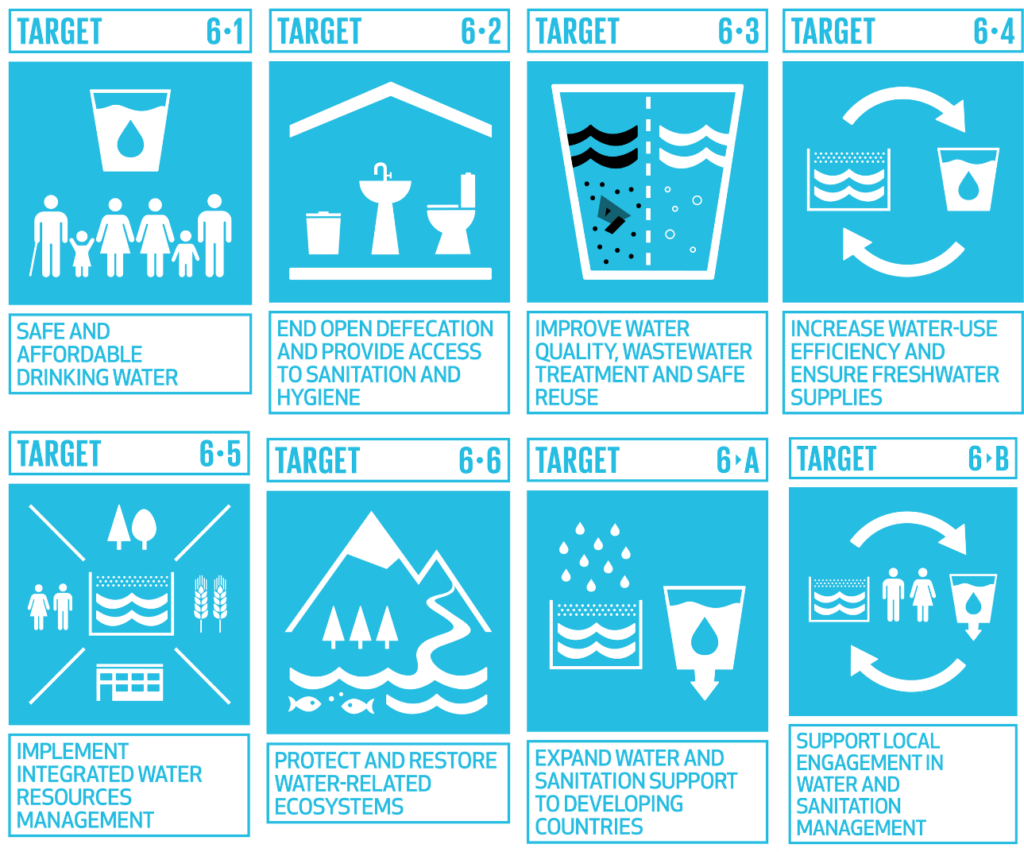

Indicator 6.2.1 (a) of the Sustainable Development Goals underscores the importance of “safely managed sanitation services” including faecal sludge management, focusing on the entire sanitation service chain, entailing containment; emptying and transport; treatment; and disposal/re-use. This is just one target out of the six under SDG 6, which are all interlinked and need to be addressed holistically as highlighted in the UN-Water analytical brief. For example, increased access to safely managed sanitation [target 6.2] must be matched by increased wastewater and faecal sludge treatment [target 6.3] if good ambient water quality [target 6.3] and healthy water-related ecosystems [target 6.6] are to be sustained. Thus, when we talk of water resources, what comes to mind and is usually given more attention is the “visible” water resources, while groundwater, an “invisible” resource, is often overlooked.

Groundwater is – and will always be – an important resource for sustaining ecosystems. In SSA, over 70% of the population relies on groundwater for domestic use, where about the same population is served by unimproved OSSs, the majority of which are in informal settlements and urban poor households. In Kampala city, less than 10% of the population has access to sewerage services while over 90% are reliant on on-site sanitation systems (OSS). In informal settlements and low-income areas (hosting 60% of the urban population in Kampala city), the most common drinking water source is groundwater from on-site water supply systems such as shallow wells and protected springs. The percentage of drinking water produced from these sources is higher (greater than 25%) compared to high and medium-income areas. In these areas, pit latrines are the predominant OSS systems and are mostly unimproved with varying quality and standards.

Questions that remain to be answered are: What happens when the pit is full? What happens when there are either no toilet facilities or the existing ones are of poor quality? What happens after the toilet is flushed?

The fact of the matter is that faecal sludge generated from the majority of the OSSs is usually unsafely managed, i.e., uncontained, unemptied, and indiscriminately disposed of. Similarly, wastewater is not safely managed due to blockages and overflows in the sewer network, and improper treatment. This results in significant public health risks and pollution of the environment, including contamination of groundwater sources and ecosystems. These challenges are more pronounced in informal settlements and low-income areas, often characterised by high population densities, high housing density, high water table, and prevalence of unimproved sanitation facilities. The risks for groundwater pollution are significantly higher in informal settlements and low-income areas which are often located in valleys with high groundwater tables (less than 5m) and less than 10m radial distance of sanitation facilities to groundwater sources, as opposed to medium- and high-income areas. Faecal contamination is the most prevalent groundwater contamination hazard due to inadequate, unsafe, and poor-quality sanitary facilities. As is frequently stated, “what doesn’t get measured, definitely doesn’t get managed”.

This must be a wake-up call to water and sanitation sector actors to institute effective regulation, data management, and monitoring mechanisms of service provision, holistically addressing all targets of SDG 6.

Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA), a government agency in charge of managing the city, including waste and sanitation services, has in the recent past made efforts to institute clear and effective regulations to enhance the City-wide Inclusive Sanitation (CWIS) approach to tackle the sanitation service delivery challenges in the city. Given the public health risks and ecosystem pollution associated with poor management of wastewater and faecal sludge, the city authority has instituted the Kampala Capital City Authority (Sewage and Faecal Sludge Management) Ordinance, a regulatory instrument, complemented by minimum standards for onsite sanitation technology options, which offers guidance to inform planning, construction and enforcement of sanitation service provision in Kampala city. These are incremental but significant steps that the city authority has undertaken, among other efforts, to realise the ultimate goal of availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Lessons learned from the International Water Association (IWA) Regulating for City-Wide Inclusive Sanitation initiative emphasise that sanitation – and its administration and delivery – is closely linked to water supply, as well as to solid waste management, drainage, land use planning, and housing development. IWA has recently launched a new initiative on Inclusive Urban Sanitation to further amplify and re-shape this agenda on a global scale.

It is, thus, undoubtedly clear that the increased risk of groundwater contamination is a significant hindrance to meeting SDG 6. This calls for an improved understanding of the status and risks posed by on-site water and sanitation systems, especially in informal settlements and low-income areas. Routine groundwater contamination risk assessment is key to preventing this. Stakeholders at all levels need to adopt more than a “business as usual” approach to accelerate progress as stipulated in the SDG 6 Global Acceleration Framework. The UN-Water Summit on Groundwater happening in December 2022 aims to bring attention to and amplify the groundwater agenda at the highest international level, noting that “groundwater may be out of sight, but it must not be out of mind”.

As we mark this year’s World Toilet Day, it is imperative to recognise the interdependency of the targets under SDG 6 from a holistic point of view, and most importantly, highlight the link between groundwater and sanitation: making the invisible, visible!